Minimal Art is a school of abstract painting and sculpture where any kind of personal expression is kept to a minimum, in order to give the work a completely literal presence. The resulting work is characterized by extreme simplicity of form and a deliberate lack of expressive content (source).

The central principle is that not the artist’s expression, but the medium and materials of the work are its reality (source). In other words: a work of art should not refer to anything other than itself (source). As minimalist painter Frank Stella once said: “What you see is what you see” (source).

Minimal Art emerged as a trend in the late 1950s and flourished particularly in the 1960s and 1970s (source). It is also referred to as ABC art, literal art (source), literalism (source), reductivism, and rejective art (source).

Through much of the 1950s, the dominant art movement in the United States was Abstract Expressionism. The expressionist artists seeked to express their personal emotions through their art.

A highly popular branch of Abstract Expressionism was called Action Painting. This was a style of painting in which paint is spontaneously dribbled, splashed or smeared onto the canvas (source).

In the early 1960’s, a new movement emerged; Minimal Art. The Minimalists felt that Action Painting (and as such, Abstract Expressionism) was too personal, pretentious and insubstantial. They rejected the idea that art should reflect the personal expression of its creator (source). Instead, they adopted the point of view that a work of art should not refer to anything other than itself (source). Their goal was to make their works totally objective, unexpressive, and non-referential.

One of the first painters to be specifically linked with Minimalism was (the former Abstract Expressionist) Frank Stella. Stella’s instantly acclaimed minimalist Black Paintings (1958-1960), in which regular bands of black paint were separated by very thin pinstripes of unpainted canvas (source), contrasted the emotional canvases of Abstract Expressionism (source).

The most prominent theorists were Donald Judd, who wrote the manifesto-like essay “Specific Objects” in 1964 (download) and Robert Morris, who wrote the three part essay “Notes on Sculpture 1-3” in 1966 (download).

A historic moment for the art movement was the group exhibit “Primary Structures”, held in 1966 at the Jewish Museum in New York. Amongst others, it featured work of Donald Judd, Carl Andre, Dan Flavin, Sol LeWitt, Robert Morris, and Tony Smith (source) and really put Minimal Art as a name on the map.

The minimalist artists wanted to allow the viewer an immediate, purely visual response (source) and let him experience all the more strongly the pure qualities of colour, form, space and materials (source). Minimalism sought to de-mystify art, to reveal its most fundamental character (source): the medium and materials of the work were its reality, and that is was what the artists wanted to portray (source). This concept of pure aestheticism was highly revolutionary at the time (source).

In order to achieve this, they attempted to remove all suggestions of self-expressionism from the art work (source), such as:

From then on, all choices stem from the intention of giving the work a literal presence:

The minimalist artists created objects that often blurred the boundaries between painting and sculpture (source). In this article, these two disciplines are still considered separately.

The minimalist sculptors were chiefly interested in how the viewer perceives the relationship between the different parts of the work, and of the parts to the whole thing. To highlight the subtle differences in this relationship (source), minimal ‘objects’ (as the artists preferred to call their sculptures) were often serial arrangements of extremely simple, geometric bodies such as cubes.

Sculptor Sol LeWitt once wrote that “the most interesting characteristic of the cube is that it is relatively uninteresting.” This comment speaks to what Minimalism aims to achieve, which is to use objects in and for themselves, and not as symbols or as representations (source).

The non-hierarchical character of the grid-based compositions challenged the notion of artistic originality (source), while the visual rhythms were strongly reminiscent of a production line (source).

Minimalist sculptures encouraged the viewer to be conscious of the space. The artwork was carefully arranged to emphasize and reveal the architecture of the gallery, often being presented on walls, in corners, or directly onto the floor (source). By eliminating the pedestal or base on which it sat, the minimalist sculptors sought to reject traditional sculpture. Minimalist sculpture shared common space as simply another object in the world. With no barrier between the audience and the artwork, viewers were forced to reconsider their relationship to the art object. Audiences could now interact with a piece on their own level, approaching, retreating, walking around it and sometimes even standing on it. (source)

Minimalist artist preferred industrial materials, prefabricated and/or mass-produced: fibreglass, Plexiglass, plastic, sheet metal, plywood, and aluminum. Steel, glass, concrete, wood and stone are also returning materials. The materials were either left raw (or hardly processed by the artist), or were solidly painted with bright industrial colours.

The result are objects of charged neutrality; objects that directly engage and interact with the particular space they occupy; objects that reveal everything about themselves, but little about the artist; objects whose subject is the viewer (source).

Well-know minimalist sculptors from the 1960’s and 1970’s:

For a comprehensive overview of all minimalist artists, please refer to my list of all famous minimalist artists, architects and designers.

Untitled, by Donald Judd (1971). Material: Anodized aluminum. Size: 6 boxes of 48 x 48 x 48 inches each. Collection: Walker Art Center.

“Equivalent VIII” by Carl Andre (1966). Material: firebricks. Size: 127 x 686 x 2292 mm. Collection: Tate Modern.

“Slope 2004” by Carl Andre (1968). Material: Steel. Size: overall 0.5 x 204 x 38 inches. Collection: Walker Art Center.

“Two Open Modular Cubes/Half-Off”, by Sol LeWitt (1972). Material: Enameled aluminum. Size: 1600 x 3054 x 2330 mm. Collection: Tate Gallery, London

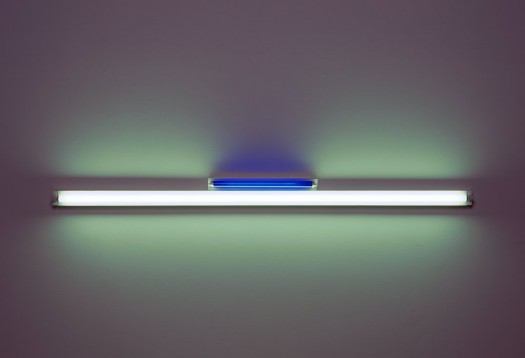

Untitled, by Dan Flavin (1963). Material: Ultraviolet, blue fluorescent tubes and fixtures. Size: 8 x 96 x 4 inches. Collection: Walker Art Center.

“Free Ride”, by Tony Smith (1962). Material: Painted steel. Size: 6′ 8″ x 6′ 8″ x 6′ 8″. Collection: The Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Like the minimalist sculptors, minimalist painters strived to create objects with presence, which can be seen at their basic physical appearance and appreciated at face value (source).

Minimalist paintings are usually precise and ‘hard-edged’, referring to the abrupt transitions between color areas. They incorporate geometric forms, often in repetitive patterns, resulting in flat, two-dimensional space.

Color areas are generally of one solid, unvarying color (source). Colors were normally unmixed, coming straight from the tube (source). The colour palette is often limited.

Through this use of only line, solid color, geometric forms and shaped canvas, the minimalist artists combined paint and canvas in such a way that the two became inseparable (source).

Well-know minimalist painters from the 1960’s and 1970’s:

For a comprehensive overview of all minimalist artists, please refer to my list of all famous minimalist artists, architects and designers.

“The Marriage of Reason and Squalor, II”, by Frank Stella (1959). Material: Enamel on canvas. Size: 7′ 6 3/4″ x 11′ 3/4″ (230.5 x 337.2 cm). Collection: MoMA.

“Harran II”, by Frank Stella (1967). Material: Polymer and fluorescent polymer paint on canvas. Size: 10 x 20 feet (304.8 x 609.6 cm). Collection: Guggenheim Museum, New York.

“Shoot”, by Kenneth Noland (1964). Material: Acrylic on canvas. Size: 103′ 3/4″ x 126′ 3/4″ (263.5 x 321.9 cm). Collection: Smithsonian American Art Museum Museum

“Twin”, by Robert Ryman (1966). Material: Oil on cotton. Size: 6′ 3 3/4″ x 6′ 3 7/8″ (192.4 x 192.6 cm). Collection: MoMA.

“Red Green Blue”, by Ellsworth Kelly (1964). Material: Oil on canvas. Size: unframed 90 x 66 inches. Collection: Walker Art Center.

There seem to have been two main criticisms levelled at Minimal Art by the dominant art critics of the day.

Firstly, that it was somehow lacking in the aesthetic qualities that art was normally expected to reveal, thus lessening the experience of the viewer.

In his essay Recentness of Sculpture (1967), critic Clement Greenberg, champion of the Modernist art of the previous decades, dismissed Minimal Art as a ‘Novelty’ art. He suggested that the ‘aesthetic surprise’ a viewer experiences on looking at ‘true’ works of art is long lasting and important, while the novelty item provokes no more than a momentary surprise that is ‘superfluous’ (source).

The second main criticism was that Minimal Art blurred the boundaries between art and the every day, and so undervalued the art object.

In his article Art and Objecthood (1967), art critic Michael Fried published a controversial and influential attack on minimalist sculpture. Unlike Greenberg who saw Minimal art as merely novelty, Fried saw Minimalism as Modernism gone wrong. He suggested that if the aim of Modernist work was to explore its medium, be it paintings, sculpture or poetry, Minimal Art had taken this investigation too far, and by referring only to itself undermined the distinction between art and non-art (source).

By the late 1960s, Minimalism was beginning to show signs of breaking apart as a movement, as various artists who had been important to its early development began to move in different directions (source).

However, critics agree that Minimalism formed a “crux” or turning point in the history of modernism, and the movement remains hugely influential today (source). For an overview of contemporary artists holding a minimalist philosophy or minimalist aesthetic, please refer to my list of all famous minimalist artists, architects and designers.

Many of the better art museums devoted to late 20th century works will have Minimal Art works in their collections.

Key collections of Minimal Art can be found at the following places: